The COP30 negotiations in Belém marked a significant inflection point in global climate governance: for the first time, the health impacts of climate change are elevated to a structured, operational, and internationally coordinated policy agenda. The Belém Health Action Plan (BHAP) positions health resilience not as an ancillary concern, but as a core component of climate adaptation, financing, and national planning.

For vulnerable countries particularly Least Developed Countries (LDCs), Small Island Developing States (SIDS), and climate-exposed middle-income regions, the BHAP offers both an opportunity and a challenge: an opportunity to unlock new systems-strengthening support, and a challenge to align national institutions with demanding implementation requirements.

1. The Strategic Shift: Health as a Central Pillar of Adaptation

Historically, climate policy has underemphasized health, treating it as an outcome rather than a driver of resilience. The BHAP reverses this logic by calling for:

• integration of health risks into Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs);

• mandatory climate-health vulnerability assessments and scenario modeling;

• climate-resilient health infrastructure standards;

• expanded epidemiological surveillance linked to climate indicators.

This represents a clear policy shift: health is now positioned as a strategic variable in adaptation planning and a criterion for climate finance eligibility.

2. The Risk Landscape: Escalating Health Burdens for Vulnerable States

Countries with high climate exposure and limited health system capacity are already facing a severe and accelerating risk environment:

• Vector-borne diseases (malaria, dengue, chikungunya) expanding into new geographical areas;

• extreme heat pushing mortality rates and overwhelming emergency services;

• air pollution and wildfire smoke creating chronic respiratory burdens;

• water scarcity and contamination increasing diarrheal diseases;

• climate-induced food insecurity worsening malnutrition and population displacement.

The BHAP’s data-driven structure recognizes that without systemic health resilience, the economic and social costs of climate change will exceed governments’ capacity to respond.

Implementation Demands: What Vulnerable Countries Must Prepare For

The BHAP outlines several policy obligations that will require significant national adjustments. Key implications include:

a. Institutional Reforms

Vulnerable countries will need to strengthen or create:

• climate-health coordination units inside Ministries of Health;

• inter-ministerial mechanisms linking health, environment, finance, and disaster management;

• regulatory frameworks for climate-resilient public health infrastructure.

b. Data and Monitoring Requirements

The plan emphasizes:

• climate-linked health surveillance;

• interoperable data systems;

• integration of climate forecasting into public health response planning.

This will require new technology, training, and long-term capacity-building.

c. Local-Community and Indigenous Integration

Countries must demonstrate community-based adaptation strategies, especially in rural, forest, and indigenous territories. The Amazonian framing of COP30 reinforces this requirement.

4. Financing: The Defining Constraint

The BHAP’s ambition depends on whether financing mechanisms evolve beyond traditional adaptation funding. Vulnerable countries will face three immediate challenges:

a. Accessing Climate Finance

The plan strongly encourages:

• integration of health components into national adaptation plans (NAPs);

• health-centered proposals for the Green Climate Fund (GCF);

• pooled financing for regional disease surveillance.

Countries with fragmented institutions may struggle to meet proposal standards.

b. Bridging the Adaptation Funding Gap

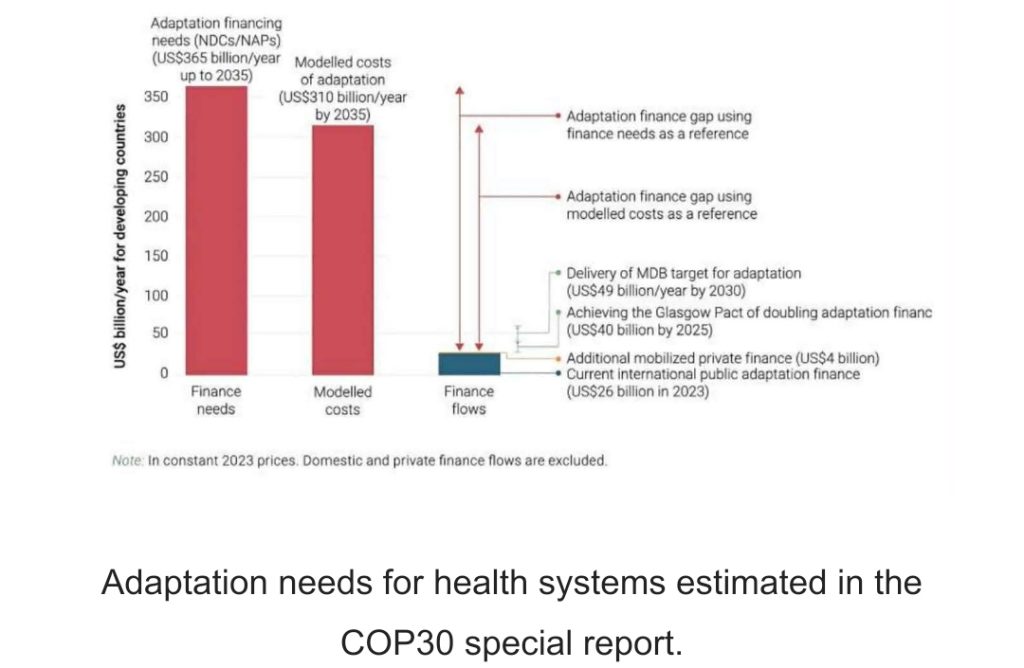

Global climate-health financing needs exceed US$30–50 billion annually—far more than what is currently available. Without scaled commitments from donors and multilateral banks, the BHAP risks under-implementation.

c. Aligning Domestic Budgets

Vulnerable countries will be expected to:

• dedicate domestic funding to climate-health resilience,

• reform procurement practices,

• and co-finance infrastructure upgrades.

These requirements may strain already limited fiscal space.

Geopolitics and the Amazonian Context

Hosting COP30 in Belém amplifies the interdependence of ecosystems and health. The Amazon region faces:

• rapid deforestation,

• climate-induced disease shifts,

• and exposure of indigenous communities to cascading health threats.

Brazil’s leadership positions the BHAP within a broader geopolitical narrative: climate-health resilience as a development and sovereignty issue, not only a humanitarian one. Vulnerable countries can leverage this framing to strengthen calls for new funding and technology transfers.

6. Strategic Opportunities for Vulnerable States

Despite its demands, the BHAP presents unique opportunities:

• Priority access to adaptation financing

Countries with credible climate–health integration plans may benefit from preferential financing windows.

• Technology and capacity transfer

The plan encourages partnerships on epidemiology, early-warning systems, and climate-resilient infrastructure.

• Regional cooperation frameworks

Vulnerable countries can establish shared disease surveillance systems, reducing individual costs.

• Stronger political leverage

Health resonates diplomatically; linking climate impacts to mortality, disease, and public safety strengthens negotiation power in climate forums.

Conclusion: A New Architecture for Climate-Health Governance

The Belém Health Action Plan signals a structural evolution in global climate policy. It requires vulnerable countries to undertake ambitious reforms, but it also opens doors to new financing, cooperation, and geopolitical influence.

Its success will depend on three factors:

1. Political commitment at national level,

2. Scalable and predictable financing,

3. Institutional capacity to integrate climate and health planning.

For vulnerable countries, the BHAP is not simply a policy document; it is a strategic framework that will shape national resilience for decades to come.