The 64th session of the United Nations Commission for Social Development did not end in a ceremony. It ended in recalibration.

From Thursday, the 4th, through Tuesday, the 10th of February, the Commission moved decisively from principle to practice. What began earlier in the week as a reaffirmation of political will evolved, over the final four days, into a rigorous examination of system design. Delegates were no longer speaking in the abstract language of solidarity. They were drafting the operational grammar of a new global care economy. At stake was nothing less than the structural redesign of the social contract.

Thursday, February 4: The Sixth Plenary and the End of Income Myopia

The Sixth Plenary Meeting marked a conceptual inflexion point. Moderated by José Antonio Ocampo of Columbia University, the discussion dismantled a decades-old orthodoxy: that poverty is primarily a function of income deficiency.

For much of the twentieth century, development policy was anchored in redistribution and transfer mechanisms. Cash transfers, safety nets, and fiscal equalization defined the toolkit. But in the compounded crises of the 2020s, climate volatility, sovereign debt distress, pandemics, and demographic aging that framework has proven insufficient.

Ms. Lee Xing of China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs articulated the shift with clarity and force. “Poverty has never been merely a lack of income,” she told the Commission, “but the deprivation of capabilities, the absence of opportunities, and the erosion of dignity.”

Her intervention reframed deprivation as multidimensional and administrative. China’s approach, she explained, relied on a national database capable of identifying each impoverished household, supported by 128,000 working teams deployed to rural villages. The model emphasized what she described as precision governance, where logistics, data architecture, and local accountability converge.

Central to that architecture were the “three guarantees”: universal access to food and clothing, safe water, compulsory education, basic medical services, and housing security. In this formulation, care systems are not residual welfare appendages. They are macroeconomic stabilizers. They prevent households from cascading back into poverty when confronted by external shocks.

The implication was unmistakable. Care is infrastructure. It underpins productivity, workforce participation, and long-term fiscal sustainability.

Friday, February 5: The Cultural and Demographic Stress Test

If Thursday was about structural economics, Friday interrogated social anthropology.

Shelly Ann Edwards of the Planning Institute of Jamaica shifted the focus from state architecture to household realities. Historically, she observed, caregiving evolved from “cultural norms of family nurture,” with women and girls performing the majority of unpaid care labor. But those norms are under strain.

Across Latin America and the Caribbean, ageing populations and rising disability prevalence are producing what she described as a mounting care deficit. Traditional family networks, once able to absorb caregiving responsibilities informally, are now structurally overstretched.

The Commission confronted an uncomfortable reality. The global care economy has long relied on invisible labor subsidized by women’s time. As female labor force participation rises and demographic pressures intensify, that subsidy model collapses.

Edwards argued for comprehensive, state-led care policies capable of coordinating financing modalities, service delivery, and accountability metrics. Without deliberate public investment, she warned, inequalities will deepen between households that can purchase private care and those forced to internalize its economic cost.

Her intervention exposed the cultural underpinnings of the crisis. Care systems cannot be engineered solely through fiscal instruments. They require normative shifts. They demand the formal recognition of labor historically dismissed as a domestic obligation.

Monday, February 9: The Seventh Plenary and the Informality Multiplier

After the weekend recess, the Commission reconvened with renewed urgency. Monday’s Seventh Plenary turned its attention to informality.

In vast regions of the Global South, the majority of workers operate outside formal labor protections. Without contracts, insurance, or pension schemes, informal workers absorb economic shocks directly. When downturns occur, they fall first and hardest.

Violet Shivut, founder of a community health workers organization in Kenya, delivered one of the most grounded interventions of the session. “I am a caregiver, a grassroots woman,” she began, anchoring the debate in lived experience rather than institutional theory.

She traced the rise of community caregiving networks to the HIV/AIDS crisis. As formal health systems faltered, grassroots women stepped into the breach. They organized. They provided services, they sustained communities, yet their labor remains undervalued.

“The grassroots women’s role in caregiving cannot continue to be looked at as targets as vulnerable,” Shivut insisted. “We need to look at what kind of leadership we are providing in the community.”

Her appeal was not limited to remuneration. It was structural. She demanded inclusion in national budget processes and policy design forums. The divide between system architects and system operators, she suggested, is one of the defining weaknesses of current care reform.

Monday’s discussions thus exposed a central tension in the Doha Political Declaration’s implementation cycle. Recognition without redistribution is symbolic. Inclusion without fiscal integration is incomplete. The informality multiplier makes care work simultaneously indispensable and precarious. Addressing that paradox is now central to global social policy.

Tuesday, February 10: Consensus Under Friction

The final day of CSocD64 was procedural on the surface and ideological beneath it.

During the Tenth and Eleventh Plenary Meetings, the Commission adopted several resolutions, including the key text on advancing social development through coordinated and inclusive policies. The Doha commitments moved from the summit declaration into formal UN documentation.

A significant debate emerged around terminology, particularly the definition of gender and the concept of intersectionality. Delegations from Iran, the Russian Federation, and the Holy See issued formal reservations. They argued that “gender” must be understood strictly in biological terms, grounded in national sovereignty and religious values.

In contrast, Switzerland, joined by Canada, Mexico, and the United Kingdom, expressed regret over the removal of language referring to “multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination.” They maintained that individuals experience overlapping structural barriers based on age, race, disability, and other identities.

The debate was not semantic. It reflected competing philosophical frameworks. One prioritizes cultural sovereignty and definitional clarity. The other emphasizes structural analysis and layered discrimination.

The Commission ultimately adopted the resolutions, but the friction revealed the evolving terrain of multilateralism. Social development is no longer a peripheral domain insulated from geopolitical contestation. It is an ideological battleground.

Nigeria’s Intervention: Bridging Rights and Policy.

Amid these negotiations, Nigeria positioned itself as a regional convener.

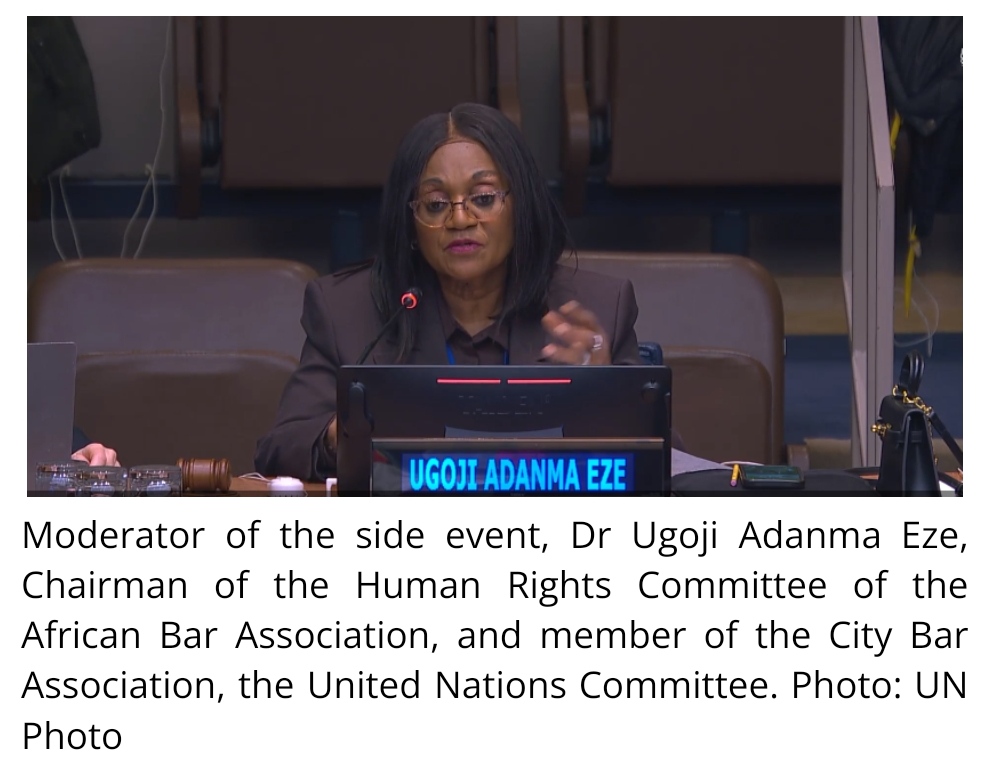

Through a high-level side event, the Nigerian delegation framed care work explicitly as a human rights issue. The forum emphasized inter-regional strategies to protect caregivers and persons with disabilities, linking social protection with legal frameworks and cultural expression.

Nigeria’s approach underscored a “whole-of-society” methodology. Social development cannot be siloed within welfare ministries. It requires cross-sectoral coordination, community engagement, and alignment with the Social and Solidarity Economy.

In doing so, Nigeria contributed a pragmatic roadmap for African implementation of the Doha commitments. The intervention reinforced the idea that the global care agenda must be contextualized within national realities while remaining anchored to universal principles.

The Closing Gavel and the Road to 2026

As CSocD64 concluded, leadership transitioned to Mr. Stefano Guerra of Portugal, who will preside over the 65th session under the theme of intergenerational approaches.

The Chair’s closing reflection distilled the moral core of the week: “As long as even one society or one country is left behind with injustice, none of us can credibly claim to have achieved our goals.”

That statement encapsulated the Commission’s recalibrated mandate. Social development is no longer peripheral. It is foundational to economic resilience and the legitimacy of multilateral institutions.