Every June 16th, the world pauses to recognize the Day of the African Child, a date marked by the struggles and sacrifices of history, and now transformed into a rallying cry for justice, dignity, and opportunity for every African child. It is a day of memory, but also a day of movement and progress. It is a solemn nod to the past and a loud demand for action in the present.

This day wasn’t plucked from a calendar at random. It was borne in the fire of resistance. On June 16, 1976, in apartheid South Africa, thousands of Black schoolchildren marched through the streets of Soweto. They were protesting an education system designed to subjugate, not elevate. The final straw? The imposition of Afrikaans (a language of their oppressors) as the mandatory medium of instruction. What began as a peaceful protest ended in horror. Security forces opened fire on unarmed children. Hundreds were killed. Their crime? Daring to demand better.

In 1991, the Organization of African Unity (now the African Union) declared June 16 as the Day of the African Child. This has a dual purpose, both to commemorate those brave students and to challenge us to do better for the generations that followed.

This day isn’t just historical; it’s hauntingly current. In Ghana, South Sudan, Nigeria, Kenya, and across the continent, millions of children still face hunger, drop out of school, suffer from preventable diseases, or fall victim to violence.

The Day of the African Child reminds us that we can’t talk about Africa’s future without talking about Africa’s children. Not as an abstract group. But as individuals with names, dreams, fears, and potential.

Every child has the right to:

- A safe environment

- Dignity

- Opportunity

- Justice

The Charter

The African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child is the moral backbone of this day. With 48 articles, it doesn’t mince words. It establishes that African children are not passive recipients of charity; they are rights-holders with claims to survival, development, protection, and participation in society.

From education and health to protection from exploitation and abuse, the Charter is a call to action for African governments and societies to uphold the dignity of their youngest citizens.

The Numbers We Can’t Ignore.

As of 2023, there are approximately 627 million children under the age of 18 living in Africa. By 2050, that number is projected to hit nearly 1 billion. That’s 4 in every 10 children on Earth.

This is not a footnote in a demography textbook; that is a whole chapter. It’s a message in capital letters: Africa is becoming the child capital of the world.

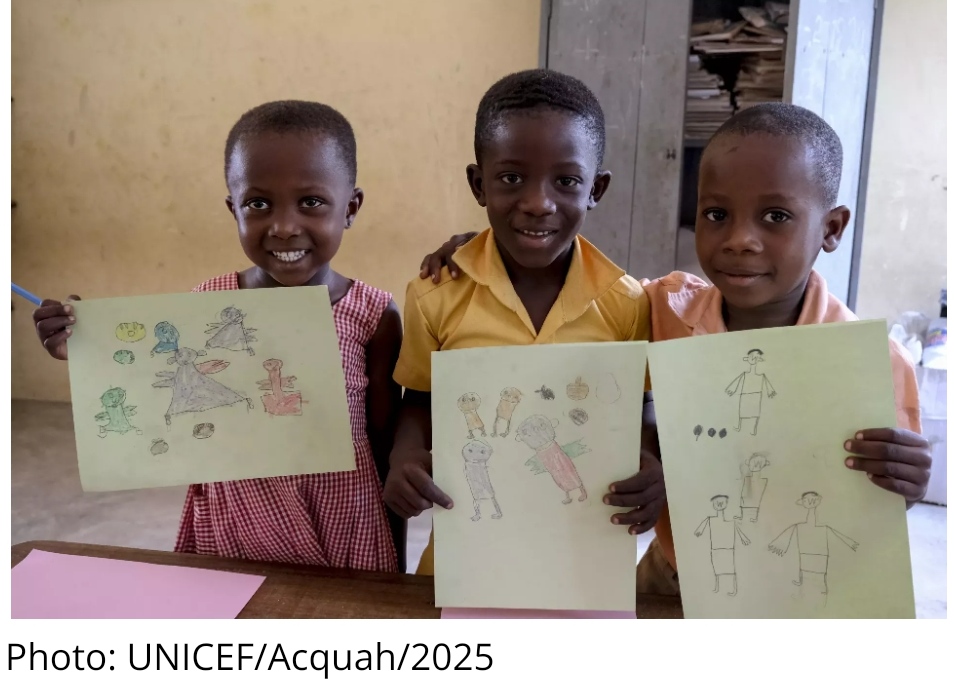

Ghana, for example, already reflects this trend. Children make up about 45% of its population. That’s nearly half the country’s future, packed into classrooms, homes, hospitals, and streets right now.

These numbers are promising for Africa, but it’s also a looming problem if Africa does not take care of its future. UNICEF Ghana says it plainly: this isn’t just about survival, it’s about thriving. That means investing now in the essentials:

- Foundational learning to build minds

- Healthcare and nutrition to build bodies

- Protection from harm to build confidence

- Digital access and skills to build relevance

- Job-readiness programs to build futures

The future of Africa is the future of the world. And the weight of that future sits on young shoulders.

The Voices of the Next Generation

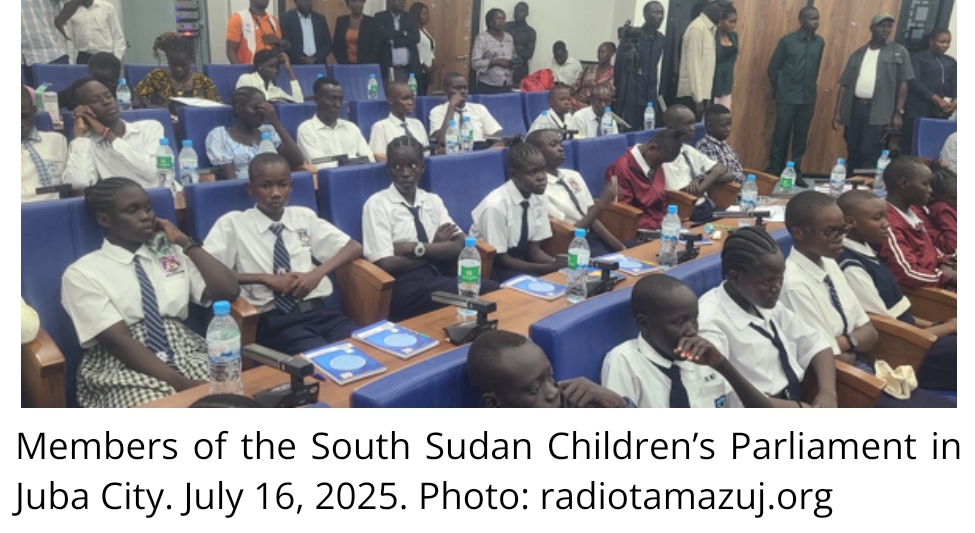

Nowhere was this urgency more palpable than in South Sudan this year. During commemorations at the National Parliament in Juba, children didn’t just participate; they led. Members of the South Sudan Children’s Parliament laid bare the crisis: underfunded schools, malnourished peers, and a government that hasn’t met its own budgetary commitments.

One young speaker, Naomi Joseph, put it bluntly:

“How can we live our lives without welfare? If you do not give the leaders food, what will they eat? If you do not send us to school, what language are we going to use when we become the leaders?”

Her voice, clear, challenging, and cutting through political platitudes, was echoed by peers like Necodemus Garang, who underscored how hunger, poor health, and lack of education are deeply intertwined. Without one, the others crumble.

The children called out their leaders, citing the country’s repeated failures to allocate 10% of the national budget to education, 15% to health, and 10% to agriculture. Civil society echoed this frustration, highlighting that South Sudan’s education budget has decreased from 5.9% to just 2.6% in the latest fiscal year. Health? A meagre 1.2%.

The Speaker of Parliament Jemma Nunu Kumba acknowledged the criticism and promised change.

“You are influencing our minds and how we should be making decisions,” she admitted. But promises aren’t enough. Children need commitments that translate into classrooms, clinics, and meals.

The Day of the African Child is not a memorial. It’s a mirror. It shows us who we are—and who we claim to be.

The children of 1976 died asking for better. The children of 2025 are still asking. The difference? Today, they’re organizing, speaking, and demanding change in their own voices.

Written by Olivier Dedingar Noudjalbaye, USA/UN Correspondent.