In the early hours of January 3, as most of Caracas slept, the rules that have governed relations between states since the end of the Second World War were quietly put under strain.

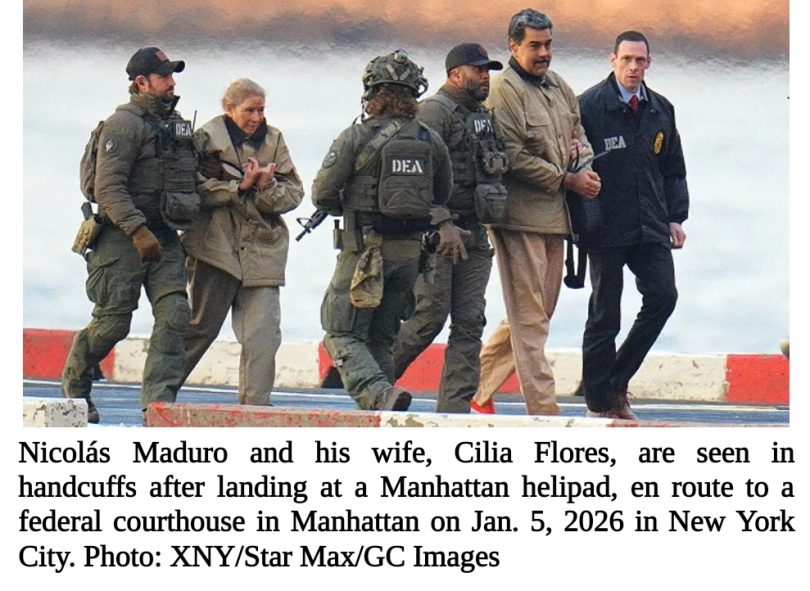

United States military forces entered Venezuelan territory, and by the end of the operation, President Nicolás Maduro was no longer in the Miraflores Palace. He was captured with his wife, Cilia Flores and detained in American custody. Within hours, officials in Washington described the action as a “surgical law enforcement operation “. The charges were familiar. Drug trafficking. Narco terrorism. Longstanding allegations that had shadowed Mr. Maduro’s presidency for years.

What was new was not the accusation, but the method. A sitting head of state had been seized by a foreign power without the consent of his government, without an international arrest warrant, and without authorization from the United Nations Security Council.

The operation has sparked intense international controversy. For international lawyers, diplomats and foreign policy officials, the moment was not merely dramatic. It was legally consequential. Had the United States crossed a line that international law was designed to make uncrossable?

A Rule Written After War

The modern international order rests on a simple premise: states do not use force against one another except in the most limited circumstances. This rule is written into Article 2, paragraph 4 of the United Nations Charter, drafted in the aftermath of a war that began precisely because force was allowed to outrun law. “The prohibition on the use of force is not a technical rule; it is the cornerstone of the UN system,” said a former International Court of Justice judge, speaking to international media. “Any military action on foreign soil must meet extremely strict legal conditions.”

The provision is blunt by design. States must refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state. Over time, this rule became more than text; it hardened into custom. It was invoked in courtrooms, debated in Security Council chambers, and treated as a foundational constraint on power.

The recent events in Caracas tested whether that constraint still holds.

There was no claim that Venezuela had invited American forces onto its territory. There was no suggestion of a joint operation that would have softened the discussion. Instead, the action was unilateral. The capture of Mr. Maduro was not an accident or the result of a grander and more legally subservient campaign. Under the Charter, such an operation is presumed unlawful unless it fits one of two narrow exceptions:

- The Question of Self-Defense

The first exception is self-defense. Article 51 preserves the right of states to defend themselves in the event of an armed attack.

In Washington, officials emphasized the threat posed by transnational narcotics networks and described the operation as a necessary response to criminal activity that had long affected the United States. Yet under international law, criminal conduct, however serious, is not the same as an armed attack.

The International Court of Justice has consistently drawn this line. An armed attack must involve a military force of a certain gravity. Drug trafficking does not qualify. Political hostility does not qualify. Even indirect support for violent actors must reach a high threshold before self-defense is triggered. No evidence has been presented that Venezuela launched or was about to launch an armed attack against the United States. Without that, the legal basis for self-defense collapses. Critics say the U.S. argument that it was a law-enforcement mission cannot mask the reality of military strikes and foreign intervention. Experts argue that if powerful nations are allowed to use force on this basis, the foundational rules meant to prevent war and preserve sovereignty could unravel.

There is also the question of proportionality. Even if a threat existed, international law requires that the response be limited to what is necessary to repel it. The seizure of a foreign head of state through a military operation in his own capital sits uneasily with that requirement.

- A Missing Authorization

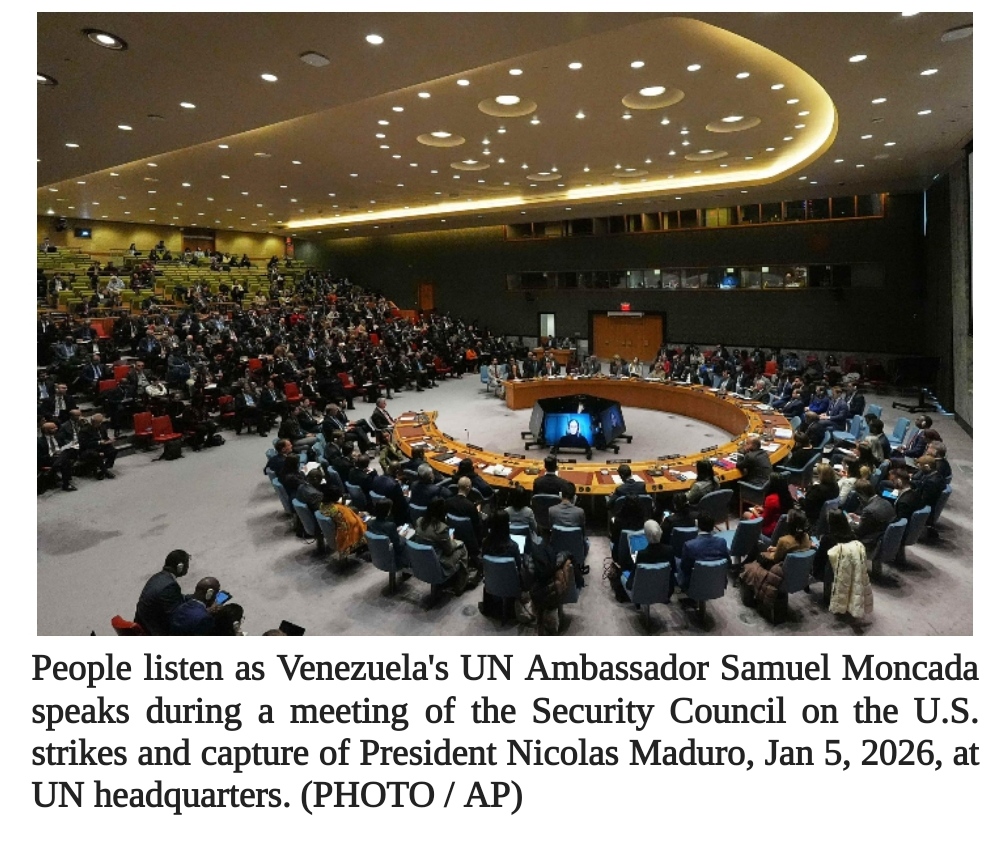

The second exception to the prohibition on force is collective authorization by the United Nations Security Council. When the Council determines that a situation threatens international peace, it can authorize military action.

That did not happen here.

No resolution was passed. No mandate was issued. The Council was not consulted in advance. The operation was presented to the world as a fait accompli.

This absence matters because the Charter in itself was designed to prevent exactly this scenario, where a single state substitutes its judgment for that of the international community. Without Security Council authorization, the operation lacks the collective legitimacy that the Charter demands.

Legal scholars have been emphatic: without a Security Council mandate, the U.S. operation appears to conflict with Article 2(4) of the UN Charter. Sir Geoffrey Robertson, former judge of the UN’s war crimes court, described the raid as “contrary to Article 2(4)” and potentially a crime of aggression.

Sovereignty, Up Close

For many states, particularly those outside the orbit of major powers, the principle at stake is sovereignty. Sovereignty is not simply an abstraction; it is the idea that political authority within a territory belongs to that state and the state alone.

The capture of a sitting president is among the clearest possible violations of political independence. It is difficult to imagine a more direct form of intervention. International law does not condition sovereignty on good governance. It does not dissolve when a leader is unpopular abroad. Those judgments are political. The law, by contrast, is designed to be indifferent to them.

By acting as both accuser and enforcer, the United States blurred that distinction.

The Question of Immunity

There is also the matter of immunity. Sitting heads of state are generally immune from foreign criminal jurisdiction. The rule exists to preserve the equality of states, not to shield individuals from accountability forever.

Accountability, under international law, is meant to flow through agreed mechanisms, international tribunals, lawful extradition and collective processes. A unilateral arrest of the sitting President of a sovereign nation immediately bypasses those mechanisms entirely.

Domestic courts may proceed once a defendant is in custody. But that reality does not resolve the international law question. How a person arrives in a courtroom still matters and matters greatly.

A Precedent Set Quietly

Under established international law principles, the U.S. strike and capture of President Maduro appear to lack a clear legal basis. Without UN Security Council authorization, Venezuelan consent, or an armed attack justifying self-defense, the operation is widely viewed by experts as inconsistent with the UN Charter and the legal norms that govern the use of force.

The immediate consequences of the operation are still unfolding. That said, the longer-term consequences may be more significant.

If powerful states can deploy military force to arrest foreign leaders based on domestic indictments, the boundary between war and law enforcement erodes. The prohibition on the use of force becomes conditional. Sovereignty becomes negotiable. For international law, the danger is not collapse in a single moment, but gradual hollowing out. “If powerful states redefine self-defense to suit their interests, the entire UN Charter system is at risk,” said one senior diplomat at the United Nations. “Other countries will follow the same logic and the rules designed to prevent war will erode.”

The events in Caracas did not mark the end of the legal order. But they revealed how fragile it has become when tested by power. The Charter was written to restrain the strong as much as to protect the weak. Whether it still does so is the question the world is now left to answer.