Homelessness in Canada is often framed as a housing crisis, a social welfare issue, or a moral failing of public policy. What is less frequently acknowledged, however, is that homelessness has become one of the most expensive and preventable drivers of health care spending in the country. The absence of safe, stable housing does not merely expose individuals to hardship. It creates a cascading set of health emergencies that strain hospitals, inflate public spending, and ultimately cost Canadians far more than proactive housing solutions ever would.

At its core, homelessness is a public health issue. Access to safe, affordable housing is a foundational social determinant of health, as critical as income, education, or access to medical care. Yet despite decades of evidence linking housing insecurity to poor health outcomes, Canada continues to treat homelessness as an auxiliary social problem rather than a structural failure with measurable economic consequences.

The result is a health care system absorbing costs it was never designed to carry.

The Scale of Homelessness in Canada

Homelessness in Canada is both widespread and persistently underestimated. On any given night, an estimated 30,000 to 35,000 people are without a home. Over the course of a year, more than 235,000 Canadians experience homelessness, a figure widely regarded as conservative due to the prevalence of hidden homelessness. This includes individuals couch surfing, living in overcrowded conditions, or staying in unsafe or temporary arrangements that fall outside formal shelter counts.

The demographic profile of homelessness further exposes systemic inequities:

- Approximately 23% of people experiencing homelessness are between 13 and 24 years old.

- Nearly two-thirds are male, though women are significantly undercounted due to higher rates of hidden homelessness.

- Indigenous people, who represent about 5% of Canada’s population, account for over 39% of the homeless population.

- One in four homeless youth identifies as LGBTQ+.

- Veterans comprise roughly 1.4% of shelter users.

- Women fleeing domestic violence account for the majority of homeless women, with earlier studies indicating that over 70% became homeless as a direct result of abuse.

Children are increasingly affected. In 2020, more than 4,000 children were living in shelters across Canada, a figure that reflects not only housing instability but long-term developmental risk. These numbers reveal a system under stress, but they do not capture the most expensive consequence of homelessness: its impact on health care.

A Costly Relationship between Homelessness and the Health Care System

Canada’s health care system is designed to provide acute and preventative care within a framework of stability. Homelessness simply removes that stability entirely.

Without consistent shelter, individuals are more likely to experience poor nutrition, exposure-related illnesses, untreated chronic disease, mental health deterioration, substance dependence, injuries from violence or unsafe environments, Inability to store medications or attend follow-up care, and many more.

As a result, people experiencing homelessness rely heavily on emergency departments rather than primary care. This is not a matter of preference, but of access.

According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, emergency department visits reached nearly 15.5 million in 2023–2024, up from 15.1 million the previous year. Among people experiencing homelessness, emergency department usage has more than doubled over the past decade, rising from approximately 141 visits per 100 people annually in 2010–2011 to over 310 visits by 2020–2021.

Emergency departments, however, are the most expensive and least efficient point of care. They are not designed to manage chronic conditions, mental illness, or the long-term health consequences of housing instability. Yet for people without homes, they become the default entry point into the health system.

As the Homeless Hub notes, individuals experiencing homelessness often seek emergency care not only for illness or injury, but also for food, shelter, warmth, and personal safety. This places additional strain on already overburdened hospitals and diverts resources away from preventative care.

Statistics Canada estimates that homelessness costs the country over $10 billion annually. These costs are distributed across multiple systems, including: Health care, Emergency services, Policing and corrections, Shelters and social services and Child welfare systems.

Yet despite this enormous burden, Canada’s federal commitment to homelessness reduction remains comparatively modest. In 2024, the federal government pledged $5 billion over nine years to address homelessness. When weighed against annual costs exceeding $10 billion, the mismatch becomes clear.

In effect, Canada is paying far more to manage homelessness than it would cost to prevent it.

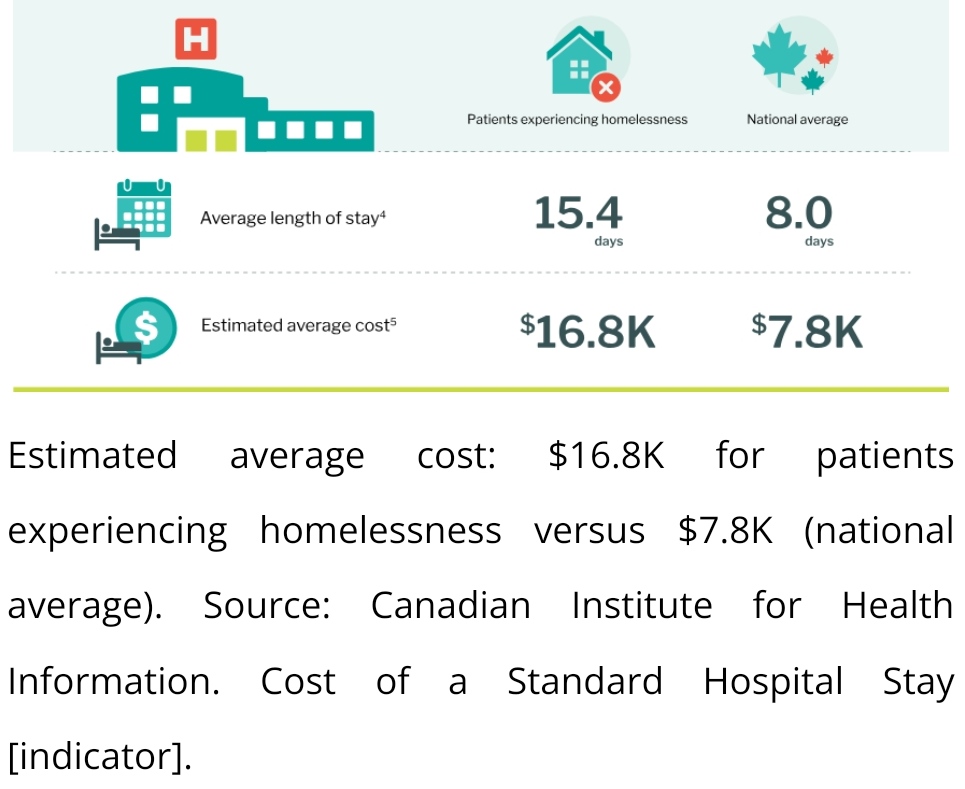

A recent study published in BMC Health Services Research provides some of the most compelling evidence to date of homelessness’s impact on health spending. Researchers examined health administrative data in Toronto, comparing people experiencing homelessness with housed and low-income housed individuals of similar age and sex.

On average, individuals experiencing homelessness incurred $16,800 per year in public health care costs, compared to $7.8k for housed individuals.

This included costs associated with emergency visits, hospital admissions, psychiatric care, outpatient services, and publicly funded medications.

Importantly, fewer than 15% of unhoused individuals accounted for hospitalization costs. Most spending occurred outside hospitals, through frequent emergency visits, outpatient care, and crisis interventions. This challenges the common assumption that homelessness-driven costs are confined to inpatient care.

Even more revealing was the persistence of cost disparities after adjusting for mental illness, substance use, and comorbidities. Even when these factors were controlled for, health care costs for homeless individuals remained nearly six times higher than for housed populations.

This directly refutes the notion that high costs are solely the result of addiction or mental illness. Housing status itself is a primary cost driver.

The Long-Term Cost of Inaction

The financial burden does not end when someone is rehoused. Research shows that individuals who have experienced prolonged homelessness often carry long-term health complications that continue to generate elevated health care costs for years afterwards.

When this reality is combined with increased emergency service use, higher rates of chronic illness, greater interaction with the justice system and increased reliance on social services, the true cost of homelessness extends far beyond annual shelter budgets.

In Toronto alone, researchers estimate excess health care costs attributable to homelessness range between $70 million and $100 million annually. When extrapolated across Ontario and Canada as a whole, the national cost likely reaches several billion dollars per year.

And this does not include costs related to policing, incarceration, child protection, or lost economic productivity.

Why the Crisis Persists

The persistence of homelessness in Canada is not due to a lack of evidence or understanding. It is the result of structural policy failures.

Since the 1990s, federal investment in public housing has steadily declined. At the same time, housing has become a primary driver of private wealth, with real estate investment trusts now controlling roughly 20% of rental housing stock in some markets.

Housing has shifted from a social good to a financial asset.

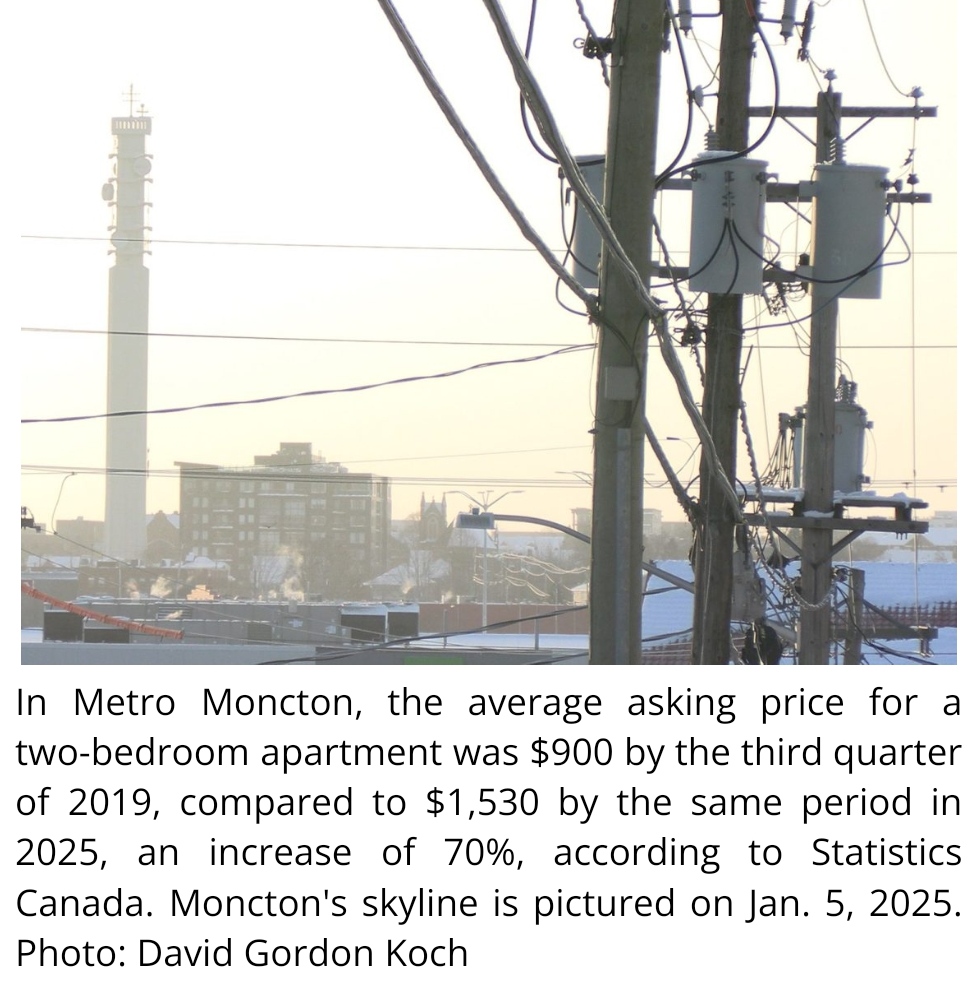

Combined with rising interest rates, low vacancy rates, stagnant wages, and insufficient social assistance, this has produced a perfect storm. Housing costs now outpace income growth in nearly every major Canadian city.

Despite this, Canada lacks a coherent de-commodification strategy for housing. Policies continue to prioritize market stability over affordability, even as homelessness rises.

Homelessness exposes a fundamental contradiction in Canada’s public policy framework. While health care is publicly funded, one of its most powerful determinants is treated as a market commodity.

Countries that have implemented Housing First models, which prioritise permanent housing with wraparound supports, have consistently demonstrated reductions in emergency service use, hospital admissions, and overall public spending. Yet such approaches remain underutilised in Canada.

Even if one sets aside the moral argument, the economic case for addressing homelessness is overwhelming.

When the full costs are considered, including health care, justice, emergency services, and lost productivity, the price of inaction exceeds the cost of intervention. Investments in affordable housing, supportive housing, and income stabilization consistently yield net savings over time.

Conclusion

Homelessness is not merely a housing issue. It is a public health emergency, a fiscal liability, and a failure of social policy.

Canada’s current approach treats homelessness as an unavoidable byproduct of economic growth rather than a preventable condition. The data tells a different story. Stable housing reduces health care costs, improves health outcomes, and strengthens social cohesion.

The evidence is clear. The cost of inaction is higher than the cost of change. Addressing homelessness is not only a moral imperative but one of the most fiscally responsible decisions Canada can make.

Written by Mohaj Salaheldin, Consultant, Humanitarian and Canada Correspondent.